The stimulus debate revisited

The debate on stimulus vs. austerity keeps covering new grounds. The former debate originated (mostly) between Krugman, DeLong, Thoma on one side, and Cochrane, Fama, Barro on the other. There was also the Alesina case for contractionary expansion and a rebuttal from the IMF with new evidence against expansionary austerity. Even though the discussion of the appropriate policy is a constant question among economists, lately the Harvard debate between John Taylor and Larry Summers and numerous blog posts of Professors Krugman and DeLong on how the austerity is ruining the European and the American recoveries, made it the key talking point once again. The focus of the debate this time is mostly around empirical research on the effects of the stimulus. While some (Talyor, Cochrane) fail to find any data to support the stimulus argument saying it didn’t do anything to help the economy, others (Romer & Romer) claim that without the stimulus, things would have been much worse for the US, with an even higher unemployment rate and a much more painful adjustment.

I see formidable arguments on both sides. The stimulus certainly did have an effect on the US economy. By helping save the automotive industry and by bailing out some banks it prevented the possibly necessary restructuring of the private sector. A good recent empirical paper by Valerie Ramey suggests that the government stimulus cannot stimulate private sector activity. It can only do so much to help the public sector. She finds strong evidence of the well known 'crowding out' phenomenon where the government spending multiplier is less than one when trying to stimulate private sector activity. As for employment, government spending helps to hire more public sector workers but it doesn't stimulate the private sector to hire more. It does however tend to have a net effect of increasing employment.

Unlike many of those who recognize this as a positive effect, I see it as an unnecessary distortion of market signals. If the finance industry grew too big, riding on consumer optimism, low interest rates, price appreciation or rising household and corporate debt than the consequences were unavoidable. Add to this the regulatory artificial demand creation that increased systemic risk by guiding banks to invest into sovereign debt and MBSs, the conclusion is that the overheated system became unsustainable. So it needs to be restructured, not by the government's allocation policies, but via market allocation policies. The market forces operate more slowly and have stronger effects, but as a result they provide more robust solutions.

The broken window fallacy

When the government creates a fiscal stimulus in order to restore confidence in the economy, it does so by creating an artificial demand for workers in alternative careers. Just like the broken window fallacy teaches us, it artificially restructures labour and capital from one industry to another.

According to the broken window fallacy, periods of war (or more precisely after-war rebuilding) can paradoxically be favourable for an economy as they drive many resources in post-war development towards high infrastructural projects focused on rebuilding the economy, which lead to high and sustainable levels of economic growth. Since there is a lot that needs to be repaired, many capital and human resources will now be reallocated from the war industry into other activities of production and use resources in this fashion. But the crucial point is that these resources could have been used in a much more efficient manner than rebuilding the economy if it hadn't been for the war. My favourite answer to all those who succumb to the broken window fallacy is: why don’t you let me smash all the windows on your house? This will create the job for the local glazier and you will redistribute your income to him. But perhaps you had different plans with your money. Now that you have to pay for your windows to be fixed, you won’t be able to, for example, take your family to a restaurant this weekend, meaning that you deprived the restaurant owner of his income.

By creating a job for one part of the economy you unwillingly deprive the other, perhaps more successful part of the economy of their income. You are sending a signal that the restaurant owner should go out of business as he won’t have any clients since they will all be spending their money on fixing their windows.

This is a vast simplification but the point is clear. When the government does the same during a crisis it sends a signal that some industries and careers should be preserved, no matter how inefficient they are. The reason is that upon these decisions rests the electoral success of a politician. So, they must be short-sighted, or they won’t be in a position to make the decision anymore.

By artificially reallocating resources this way, a fiscal stimulus slows down the creative and innovative processes of the market economy. A fiscal stimulus can only help an economy retain its pre-crisis status quo. It will not help it nor guide it towards establishing a new equilibrium. Any growth it creates will most likely be 'jobless growth' in which the private sector didn't respond properly to the distorted allocation signals.

"Patterns of sustainable specialization and trade"

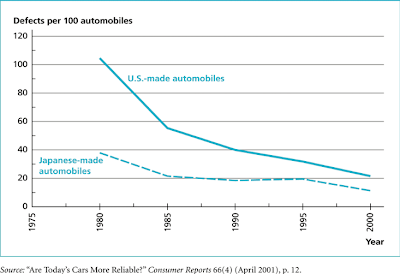

In an excellent paper for the Adam Smith Institute, Arnold Kling devises a theory on how signals in the market send information on the efficiency of each industry. Since new production technologies are unknown, one must take time and effort to discover them and develop new production technologies and processes. Patterns of sustainable specialization and trade will create new market signals that will give headway for new industries to arise and restructure the job market. New skills will be required and new occupations will be created. For example, think of the occupations such as typewriter repairman or telephone operator. These employed a lot of people, but were they bailed out by the government when a new industry came along? I'm not saying the US automotive industry (for example) was going to be replaced anytime soon with a transport device faster and more efficient than a car, but it was a clear signal that US car manufacturers were apparently doing something wrong. Just look at this graph that compares the US and the Japanese car industry:

|

| Source: Weil (2009) Economic growth. Pearson International Edition |

That's essentially the point: if something is not efficient enough, something more efficient will replace it. And the decision of how this should be done shouldn't come from the government but from entrepreneurs.

The finance industry on the other hand was caught up in a bubble. The exit strategy was an immediate bailout, but for whom? Only for those companies that invested enough in political campaigns. The result of the bailout was another huge distortion sent to the market. The end effect of stimuli and bailouts can only set a trigger for another business cycle bust. Forget about the short run - the best 'short run' policy for the future generations is a policy focused on long-run stability and clear signals sent to the market on who to hire, in what to invest, in what to specialize in and so on. Otherwise we simply create more problems in the future. When you're thinking about sustainability and stability, think about the long run. To conclude, as Kling puts it:

“...government spending is not likely to solve the problem. Government jobs are not self-sustaining. Instead, they require subsidies from present taxpayers or, if the spending is deficit-financed, from savers (and, ultimately, future taxpayers) ... The restoration of patterns of sustainable specialization and trade will have to come from the private sector. Short-term so-called stimulus programs may impede the necessary adjustment, rather than hasten it.” (Kling, 2012)

Very good text and an excellent point! I have to read the Kling paper in full, but from this I understand that it's a reassurance of Smith's ideas in the modern business cycle theory.

ReplyDelete"That's essentially the point: if something is not efficient enough, something more efficient will replace it. And the decision of how this should be done shouldn't come from the government but from entrepreneurs."

ReplyDeleteI agree! And I would add that any intervention of the government is never considered to improve efficiency. The best proof of this is anything publicly owned in comparison of the same thing being privately owned.

I don't subscribe to all this nonsense that if there was no stimulus, thing would have been better.

ReplyDeleteWhat do you propose, just let everything go bankrupt? How would that be helpful? Unemployment would be twice as big as it is now and forget about the good results the economy is producing. Cause according to the most recent data, it actually IS recovering. Estimates are of a 3% growth this year. The austerity chained Europe can only dream of this kind of growth. Europe is the real proof that austerity doesn't work.

You can't prove that it would have been better or that it would have been worse since it didn't happen. You can only assume what would have happened.

DeleteThe same thing goes for your unemployment claim - how do you know that it would have been "twice as big" by now? Perhaps the restructuring would have been done faster, within two years and we would be experiencing much stronger growth now. Besides, since you're on the subject of the pace of the recovery, please note that this recovery is one of the slowest ever: http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702304760604576425793342142396.html?mod=WSJ_hp_LEFTTopStories#articleTabs%3Darticle

Yes, Yes, I do actually think just letting everything go bankrupt would have been better. You see, that is what the bankruptcy laws are designed for. Companies can reorganize, pay part of their creditors, and reemerge with much needed changes.

DeleteInstead what we got was endless market distortions that even now retard growth.

Mike, yes, in a way I believe that was the initial idea.

ReplyDeleteAnonymous, Charlie provided you with a good response, so I'll just add to that the main point of the Kling paper I was quoting: market signals determine the optimal levels of production.

"Since new production technologies are unknown, one must take time and effort to discover them and develop new production technologies and processes. Patterns of sustainable specialization and trade will create new market signals that will give headway for new industries to arise and restructure the job market. New skills will be required and new occupations will be created."

All this, of course, takes time and this is why my emphasis in the conclusion was on the long term response to the crisis, based on proper and undistorted market signals which will undoubtedly result in a higher steady-state income.

Fiscal stimulus on borrowed money is almost necessarily a negative, for all the reasons given, including crowding out and distorting the market. . . But hiring more government workers also has it's on inherent negative effect. Civil Servants at the federal level only rarely do work that helps the economy. More likely they will be engaged in promulgating an ever expanding pool of regulatory burdens.....

ReplyDeleteNow, if stimulus consisted of moving ahead on necessary infrastructure projects using saved money then it might have the actual multiplier effect that Keynes originally conceived of. But, of course modern governments never save money and never make sound spending decisions, only political ones.

Yes, very good point. When political allocation of resources overrides the market allocation, the equilibrium outcome is inevitably much less efficient than optimal.

DeleteFrom this blog i got my accounting homework answers free and these are so valid and helpful.

ReplyDelete